Social Practice

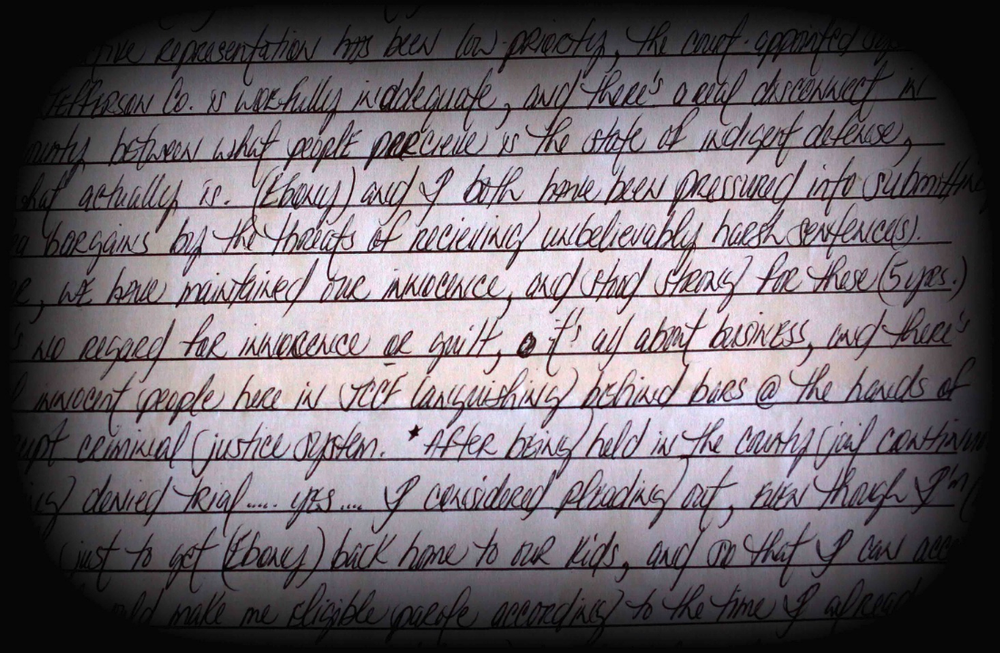

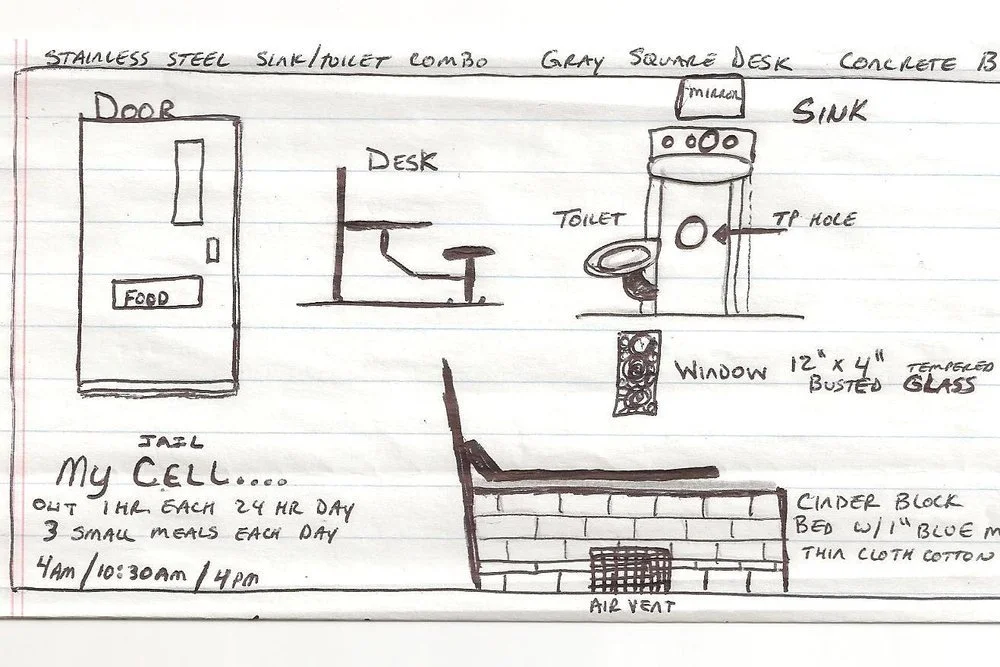

In Texas county jails, thousands of people await trial in dangerous and inhumane conditions. They suffer human rights abuses that can lead to disability and death. These thirty urgent voices of incarcerated people and their loved ones tell their own stories—a poignant appeal for changes to the criminal justice system gives that an inside look.

I was honored to work with the Texas Jail Project to help curate this collection of brave voices.

"An admirable, all-volunteer effort to document the lives and experiences of New Orleans evacuees. Alive in Truth is a thorough, big-picture exploration of the toll of one of America's worst natural disasters through the eyes of its victims - an invaluable historical tool."

— Austin Chronicle

This toolkit for facilitators offers 12 media arts lesson plans for resisting social oppressions such as sexism, racism and homophobia, with teen learners. It offers an intersectional approach to transforming culture and uses student art to foster dialogue on crucial issues.

by Abe Louise Young with the Prevention Team at Texas Council on Family Violence

A collection of feature articles, interviews and youth work that explores the vital powers of the writing process, and how to teach it. Includes the collection, Half My Heart Is In Iraq: Students with Deployed Parents Speak Out.

My Dreams Are Not a Secret: Teenagers in Metro Detroit Speak Out

Next Generation Press

An anthology of writing on race and identity by a diverse group of teenagers in metropolitan Detroit. The anthology emerged from an intensive writing workshop for students of Hmong, Arab and African-American descent. Facilitated and edited by Abe Louise Young with What Kids Can Do, Inc and the University of Michigan Youth Dialogues on Race and Ethnicity.

Articles on Human Rights, Mutual Aid & Disaster

New Seeds for Old Stories: On Defending Palestine and Rejecting Zionism as an American Jew

The Most-Read Essay on Vox Populi in 2024

“I cannot celebrate or sing about this plot. The words that rise up are unfair, unjust, unholy. How do we turn the hands of history, interrupt the seige? Israel, this is not the way home. Israel, we must look in the mirror. Yes: descendants of a holocaust immediately created another holocaust: oh painful, terrible truth. Oh repetition compulsion.”

“Hurricane Katrina did not happen in a vacuum, in America’s imagination, to everyone, or in general. It happened in a particular geography, a history, an economy, and a field of race and power built to render certain people powerless. When a white person takes the voices of people of color for his own uses, without permission, in the aftermath of a racially charged national disaster, it is vulture work—worse than ventriloquism.”

Raped By The Deputy:

A Texas Case, A U.S. Problem

by Abe Louise Young & Katie Matlack

On Dec. 27, 2015, a sheriff’s deputy, armed and on-duty, raped a female inmate in the parking lot of the county jail in San Antonio, Texas. Six days later, the woman reported the assault. Her allegations could have easily been ignored, but for one detail: security cameras had recorded the attack in the jail transport van.

Deputy Erick Montez, 35, was arrested on January 12 and held on felony charges of sexual assault and violating the civil rights of a person in custody.

At fifty hotels across Austin, continental breakfast lines are bustling. Families wake up early to try to cram in enough Pop Tarts, muffins, cereal, and milk to hold them until the next day.

These are the recipients of vouchers from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which have given families temporary housing in hotels across Austin after their homes were destroyed by Hurricane Harvey.

In the first few days after BP’s Deepwater Horizon wellhead exploded, spewing crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico, cleanup workers could be seen on Louisiana beaches wearing scarlet pants and white t-shirts with the words “Inmate Labor” printed in large red block letters. Coastal residents, many of whom had just seen their livelihoods disappear, expressed outrage at community meetings; why should BP be using cheap or free prison labor when so many people were desperate for work? The outfits disappeared overnight.

Letter Art Installation, Gallery Exhibit &

Public Letter-Writing Project

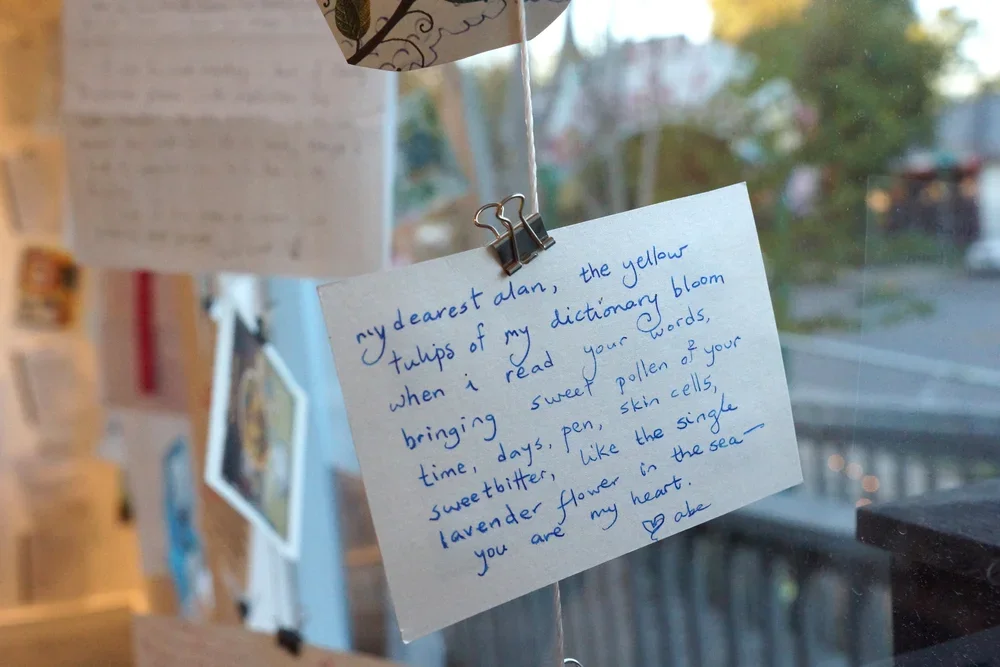

Poet-to-Poet: A Friendship in Letters

Chicago poet Alan Shefsky and I wrote to each other nearly every day for thirteen years, and exchanged over 3,000 intimate, playful, often-rhyming letters and ephemera. Alan died in 2014. At that time, I created an art installation that displays 200 of those mailed pieces, which viewers can read and touch. It also offered a public letter-writing station filled with letter-writing prompts. Visitors wrote over 400 letters, which I stamped and mailed to their recipients all over the world.

Read the Chicago Tribune article by Mary Schmich:

For 13 years, 2 friends wrote letters daily. It was a love affair of poetry, separated only by death.

Personal Story

I was born in New Orleans, Louisiana and grew up listening to people speak to strangers with love and abandon, pleasure and pain.

I also grew up listening to intolerable inequities in power, wealth and freedom. At 12, I joined a group called ERACISM that met at the public library and got my first taste of mutual aid and creative, neighbor-to-neighbor activism for cultural change. It was an interracial, cross-class group of people from 12 to 78, figuring out how to resist racism. I was hooked.

Very young, I was aware that I was different—queer, lesbian, backward. To be openly gay was to risk your skull in that era. This led to me wanting to find all the old lesbians and gays I could and listen to them talk and laugh.

My childhood home had equal measures of love and violence, nurture and abuse. I got solace by sitting in Charlene’s, a French Quarter lesbian bar after school, drinking orange juice and doing homework. I ran away from home at age fourteen. After some time on the street, I was invited to live at the New Orleans Zen Center, an urban monastery. I stayed there as a resident meditation student while I finished high school.

I received a scholarship to Smith College and left Louisiana for rural Massachusetts. There, I was fortunate to be mentored by poet Elizabeth Alexander and to help establish The Boutelle-Day Poetry Center in 1997. Every few weeks, we got to listen to and dine with a poet who burned with intense personal needs to speak in image, to stitch metaphors and offer them as music, to keep broken things. I got to see what it meant to live your truth. I got to witness vulnerability being a gift, not a danger.

My independent course of study focused on arts and literary resistance to 2oth century totalitarian regimes. This brought me to Denmark as part of a human rights fellowship to interview elderly fishermen who’d saved the lives of their Jewish neighbors during the Nazi Holocaust by rowing them to Sweden.

The fellows on this project studied oral history collection at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. I never forgot the voice of a woman who hid in a barn for two years when she was small, mothered only by a cow. After the war, she wore a cow pin on her blouse every day for the rest of her life. She fingered it and her voice cracked, an eighty year old recalling being eight.

The next year, I created a volunteer literacy program using creative writing as the teaching modality in a medium-security men’s prison in Chicopee, Massachusetts. I thought people might learn to read and write more easily if they were telling their own life stories. I knew by then that using words to make sense of trauma did healing work on multiple levels.

It wasn’t just the writing, telling, or hearing — it was the electrical conductivity between the person sharing the story and the person recieving it. Like putting the particles of the experience into a solution that became light between them. Light that let to movement, an increased sense of trust and safety in the arms of life.

After college, I worked at a homeless shelter in Oakland and spent a year on a lesbian land trust in Mendocino, California, being in home community with women activists in their elder years. It was healing to live under the redwood trees, sing feminist songs shirtless around the campfire, drink well water and learn about aging in poverty and freedom.

I was lucky to have been named a Beinecke Scholar, however, and needed to skedaddle back to school to use the graduate award. Use it or lose it. I moved to Chicago and got an M.A. in Performance Studies at Northwestern University, studying Black Feminist Theory, political theater and contemporary women’s poetry. I lived in a tenement held together by duct tape and volunteered at the Marjorie Kovler Center for Survivors of Torture. I wanted to learn how to talk with people who’d undergone things impossible to explain; how to make space for sharing without ever asking a direct question. I learned a lot about avoidance, dark humor and how to make space for emotions beyond control, mine included.

I left Chicago for Austin to pursue an MFA in Poetry at the James Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas. I worked as an education journalist for a nonprofit media newswire that increased positive representations of teens of color, and taught writing workshops in public schools from Alaska to Alabama. I graduated from the MFA program and published my first anthology of work by young writers just as Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans.

It seemed I couldn’t run away from my past or family; they came to me. Unable to rest, I got friends together to set up community listening stations with survivors and volunteer therapists. This became an oral history and relief project called Alive in Truth, documenting the full lives New Orleanians in public housing before the flood, and helping chart their path in Texas. We were able to assist more than sixty families in getting apartments, furnishings, FEMA aid, clothes and bus passes, as well as little essential things like dentures, glasses and picnics with other evacuees.

After a year of this relief work, the FEMA money ended and most of these families were made homeless again. The donated furniture was repossessed. I had a nervous breakdown. To stay alive, I had to crawl into a trauma treatment center in New Mexico for six months. My own loud early wounds became deafening when my promises to others couldn’t be kept. I had to be still, feel pain and learn my limits.

Sitting in silence with others, then putting words to shame and buried selves taught me patience. I learned that almost everyone has suffered indescribable loss. The human mind is infinitely creative. It comes up with endless ways to ignore fracture and keep going on. In time, I recovered enough to feel I had the right to stay alive. But I had to do it with the currency of stories.

My path was set ~ I wanted hold space for people to talk about what they’ve loved and lived through and find reasons to keep reaching on. I could help put words down, bring the words to others, make them public; build truthful power together to make structural change.

By day, I spent fifteen years as an educator and communications director in the movements to end intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and abuses of children. By night, I worked as a writer, writing coach and editor. I led writing workshops in my living room from 2005 to 2020. Now, I am fortunate enough to work work full-time with people and words.

We hunger to communicate the same way fruit hungers to be eaten, kids long to be watched doing their fancy jump and money hungers to be shared. Poet Marge Piercy writes, The pitcher cries for water to carry / and a person for work that is real.

Right now, I’m focused on talking to people living outside, without a roof besides a tarp. Without a sense of safety or continuity in place or people, what do they do? What help do they need? (Besides economic justice, racial justice, gender justice, migration freedom, freedom from violence, education, food, water, medical care, and all of their human rights?)

I’m grateful to have the chance to still listen and learn from people speaking about their specific unique lives with love and abandon, pleasure and pain, honesty and hope. I hope to be a faithful witness and to lift up as many voices as I can.

Social Practice Projects